| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

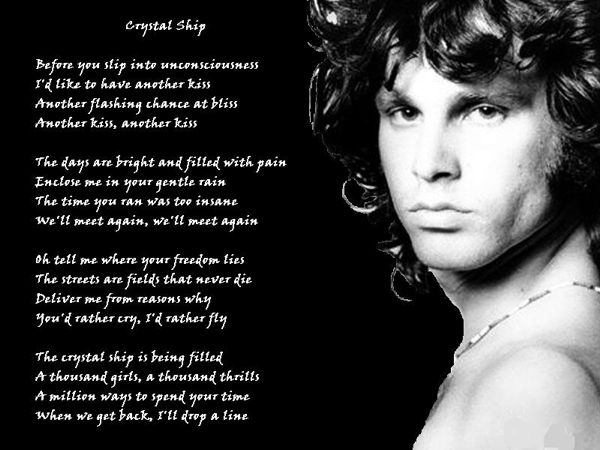

BETWEEN WATER AND THE SKY:

THE CRYSTAL SHIP'S MEANING AND CONTENT

by

Sonia de Pascalis

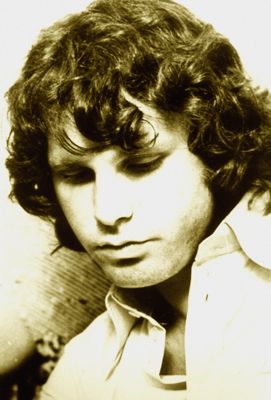

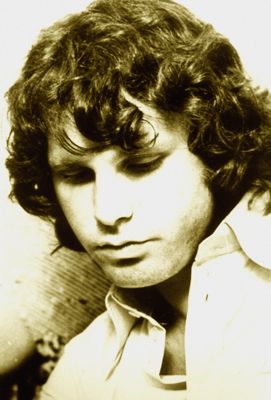

Once,

among some of the Doors admirers, a question rose on what

exactly the 'crystal ship' ’s poetic figure

represents.

I came up to some considerations, which I would like to

share on this honored magazine.

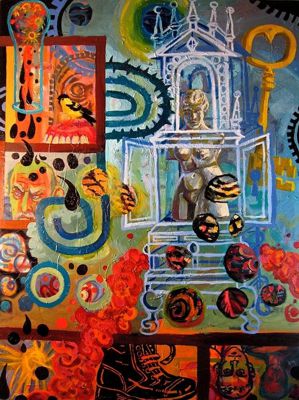

The image itself represents a man's soul seen like a

solid, fragile, sensitive, perceptively pure and

transparent body,

but also a mystic vehicle, both individual and

collective, for reaching the world of total experience of

reality.

This ship, to me, seems to be able to travel through both

sea and air, like in a nightly shrouded great ocean of

darkness.

And here the story begins....

It is made of crystal which, be it natural or handmade,

is a mystic material connected to vision and associated

to the power of purifying, empowering and filtering

spiritual energies and vital forces.

The purified senses stand in the transparent and lucid

crystal which also usually shines in glimpses.

On one level, the ship is a symbol of the poet's soul,

sailing away successfully, although through suffering,

from a sentimental world of defeat, after the breaking up

of a loving relationship, despite whatever will

become of his lost partner.

But there is more than this, another level of meaning,

philosophical and empirical.

In this other dimension, on one hand, the crystal ship

is still the metaphor for the soul itself, but seen

outside of the

sentimental realm: it is a person's spirit, sailing pure

through an experience travel and towards the paradise

world

of total vision of reality.

Somewhere it has been said that this ship has the

capacity of reading in its helmsman's mind...

On the other hand the ship is a collective vehicle: it is

a medium that calls the soul, leading to the vision, like

during the

journey, like at the end of it. This paradise, the final

destination world, can be opened by collecting every

experience made

during the journey and at the same time it is built

gathering together the results of many experiences,

levels and states

of consciousness from a single person and from a group of

people: the ship is made for and from getting together

such

individual states of mind and perception.

As a vehicle for the spirit, it is the pure and

transparent means allowing the vision of the world

outside,

and to filter and store on board things that a passenger

relinquishes along the travel.

On board you find people and other ways of experiencing,

feeling and having emotions.

But these things are, at the same time, belonging to

three different levels: first, things you get by the ship

itself, second,

experiences stored inside it, from the outside world

along the trip. Finally, they are also adventures that

happen in life on

board with other travel mates.

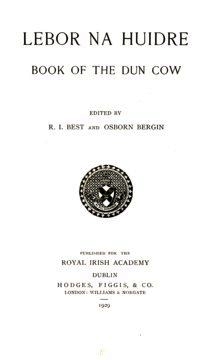

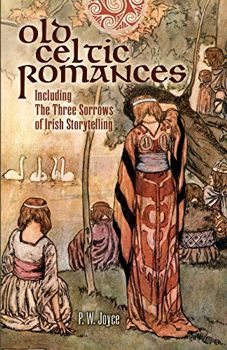

Jim Morrison directly revealed that the image of the

crystal ship was taken from a figure named in 'Connla'

's tale,

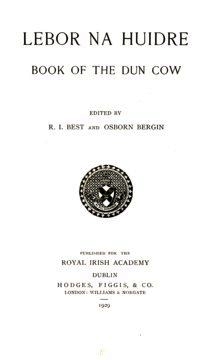

a legend contained in the ancient Irish 'Lebour na

hUidre' (in English: 'the Book of the Dun

Cow'), and from there it takes its

basic meaning of a sacred and mystic vehicle to a

paradise world of blessed experience, populated, among

the rest, by

thousands of women. The most that is renown about this,

is reported by Chuck Crisafulli in his 'Moonlight Drive:

the stories

behind every Doors song'. He says Jim talked with

Patricia Kennealy-Morrison about the celtic derivation of

'the Crystal Ship'

theme, that he knew Connla's legend and that it

came from 'Lebour na hUidre'. I can't say if he

actually read the original

story, called 'Etchra Condla Chaim meic Cuind

Chetchathaig', included in 'The Book of the Dun

Cow', or just some report of it,

which anyway are rare and precise. From the clues, Jim at

least got it from from a very faithful version, probably

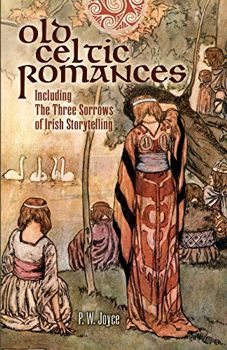

'Connla of

the Golden Hair and the Fairy Maiden' by Patrick

Weston Joyce, who in his book 'Old Celtic Romances'

revealed the legend's

origin and gave its reference. Morrison grabbed the

original to some extent, or really read it too. One of

the reasons is that

Connla's story comes from two ancient manuscripts,

but in Morrison's case, just 'the Book of the Dun Cow'

is always

reported. I only doubt the availability of its readable

copies outside Ireland. Anyway, he knew enough of it, and

so I'll name

the tale Jim meant as 'Etchra Condla' 's.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

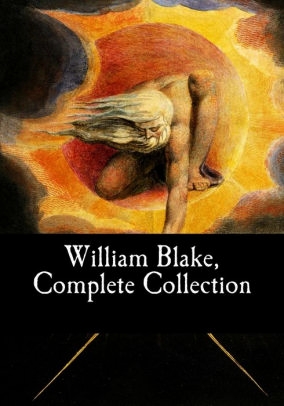

Morrison sees in

that crystal vessel a means of perception and knowledge,

that also enshrines in itself a world of

perfected experience, which there isn't in the original

tale. He sees it as the paradise of cleansed experience,

in

William Blake' s and Aldous Huxley's perspective.

Speaking strictly about the Crystal Ship's figure,

analogies with Blake’s poems are limited to the

theoretical aspect,

and just to a superficial direct reference: it is highly

presumable that Morrison slightly made the

superimposition

between this author's world and the tale of Connla,

before he wrote the text which would become the lyrics

for the

Doors song ‘The Crystal Ship’.

In fact, he had already done it while reading 'Etchra

Condla' 's tale for the first time, in some moment

before finding

himself involved in a particular happening, which

triggered and produced the very intuition and composition

of 'The

Crystal Ship' itself.

But just in that

very moment he kind of came to the real understanding of

what, to him, the crystal ship of 'Etchra

Condla' was.

The ship of

visionary experience itself was taking shape in front of

his eyes. Only now he experienced and

understood

it fully. Many Doors admirers know that this image, and

maybe the whole poem, was inspired by the lights of an

oil

tanker or plant, which Jim saw offshore either of isla

Vista, a littoral of Santa Barbara's (urban legend

strongly says,

or wants to believe), or from one of the L.A. beaches

(Santa Monica or even Venice itself).

He saw these lights floating in the deep darkness of the

all-in-one abyss of the nightly ocean and sky, altogether

fused: in that very instant he must have done the match.

In fact, the scene could only immediately recall him the

mystical ship of Connla, the curragh (which

in the story is

actually called a boat, and more often a canoe: 'strong

and swift', in Joyce, Noi Glano – Curragh of

Pearl / Loing

Glano – Curragh of Crystal', in 'Etchra

Condla').

A 'Straight gliding, strong, crystal canoe'

which can protect prince Connla 'from druids and the

demons of the air',

since, like Crisafulli smartly described it, it is

capable of flying, more than sailing, over sea or land,

during his travel

towards a Fairyland (Mag Mell – the Plain of

Delights). This land, in Celtic tradition, is an

eternal realm after death,

accessible to the sacred kings, like Connla. Religiously,

Connla represents the immortal part of the king's soul.

It

was believed that if this part of the king's soul went to

reside forever in that realm, it would allow the rest of

his

spirit to be reborn into his kingly successor in the

earthly world.

Jim had probably already made the match between this

paradise, plus the crystal ship as a container, and

William

Blake's concept of Belulah, the heavenly dimension

attained by 'breaking through' (which is not a concept

namely belonging neither to Blake, nor to Aldous Huxley).

Besides that, in their imagery these things are

represented with some precise objects, but there are no

ships.

That night, Jim was on his way to make up his mind about

his break up with Mary Werbelow.

Both the Irish tale and a particular poem of William

Blake, the Crystal Cabinet, involve the sensual

relationship with

a woman as the medium to access this paradise world, and

the crystal object as the instrument in their pertinence,

to accomplish it. And so the match was made. But Blake

talks about a partially betraying and false love

intercourse,

and Morrison rewrote his own idea of the story told in

the Crystal Cabinet in all the first part of his

poem-song, the

only one where he actually talks about Mary and him.

Things change when the crystal ship's vision comes

in: it suddenly tells another story from Blake's, and it

follows

the only reference Jim willingly recognized, Etchra

Condla.

Surely, from the very first time he met the Irish tale,

he had been knowing that the crystalline dimension that

Blake

does use in his imagery, to him, were more likely a ship,

than anything else.

But until that very moment on the beach, he hadn't

visualized it so clearly and definitely.

Suddenly ... it appeared the real presence of an

enlightened structure in the floating black ... and Jim

saw the whole

thing from a totally different aspect than Blake's

imagery.

Just focusing the scene amidst the ocean, he understood

that for him the purified senses and their perceptions

container where nothing but a ship, sailing exactly in

that way, no matter how his literary mentors represented

them.

And now it was just manifesting itself in front of his

eyes, together with all his romantic struggling for the

end of his

last long term love relationship.

In the same way, he was aware that where Condla's

canoe differed from Blake's concept, it had all the

characteristics

of Rimbaud's intoxicated boat.

The curragh is not just the sea godess

Manonnan's boat / womb, but it knows and moves

according to its passenger's

and conductor's mind.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

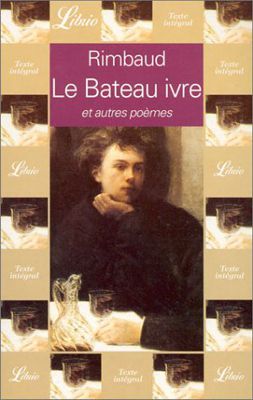

Like the Irish

legend, both Rimbaud and Morrison use a boat to

symbolize a place of totally free experience and

perception,

and at the same time the experimenting soul and senses of

the poet.

In 'le Bateau Ivre' ('The Intoxicated Boat'),

Rimbaud metaphorizes himself as the vessel, whose body

dips in and directly

absorbs the effect of the sailing experience.

In Morrison's case, the self identification with the ship

is also the natural consequence of the fact that it comes

out in the middle

of him writing about his feelings for parting from Mary:

it springs out by a subjective, first person and

sentimental stream of

consciousness, and thus he visualized it in this

particular way.

The ship is Jim's own reaction to the situation he was

living, absolutely opposite to what Blake represents in The

Crystal

Cabinet. Jim's ship represents the world of

imagination and experience, and not love anymore. It is a

declaration of taking

possession of freedom from the restrictions of moral and

of control, exactly like it is in the Intoxicated Boat.

But the presence

of Rimbaud in this poem is so fused to Morrison's concept

of the ship, that it is neither quoted, nor imitated.

It is embedded and embodied in the ship's image itself,

and replaced directly by the author's own original

vision.

When he was

inspired to write this poem song, anyway, Morrison

figured it out as an expression of Blake's general

concept:

there is a world of cleansed vision of things, accessible

by man in certain states of mind or during certain life

experiences such

as, also, love relationships, sexual intercourse and

their effects (for Jim the ship in the Book of the Dun

Cow automatically

meant this).

But Morrison's crystal ship has another original

characteristic, both in front of the Irish tale and of

Blake's: the protagonist

identifies his own spirit with the ship, but at the same

time he sees himself as its passenger. A totally

unprecedented

association of both these aspects together.

At the climax point, conditioned by the sight of an

enlightened ship or plant offshore in the ocean, in

reality outside, he

identifies himself with it, in this double sense.

Another original aspect of Morrison's ship: it is a

collectively built medium, that picks up a group on

board.

A shared medium of vision, of experiencing and storing

knowledge together with one another, which he'll

represent again in

The End’s ‘blue bus’ and

other symbolical vehicles scattered throughout his lines.

John Densmore has suggested that the ship represented the

Doors themselves: he totally grabbed its core meaning,

though

I wouldn't namely identify it with the group itself.

It surely represents the music and the artistic project

that they were building on: creating a conceptual and

spiritual vehicle for

opening minds, as his personal example to indicate a

universal collective medium for accessing the hidden

realities which

lead to interior rebirth or resurrection during life

course. The crystal ship is more than the music:

it's the Doors songs, and

among the passengers, the musicians are the crew

(again... The End: 'driver where you're taking us',

meant like acid but also

and mainly like the drivers of the music bus calling the

audience: them four). More, 'it is this song',

forming the crystal ship in

people's minds, bringing people on the trip: it builds it

up, fusing Jim's love loss feelings with the outbreaking

world of all

experiences that he has had and that he is having. This

way, he sails away from 'Mary's womb', with his soul

untouched, nay,

forged by their own sad epilogue, though thru' the sea of

sorrow and parting. This vehicle, created by the song,

with the crystal

ship evocation at its core, makes of his experience with

Mary too, one of those, although a main one, which and by

which his

soul's ship, and the ship of collective experience, is

being filled.

I would say it symbolizes the context and texture of

their artistic progress, in which Jim saw himself and the

others involved

and dipped (or 'drowned'...) in.

But Jim's intent went beyond it, over the material and

subjective identification with the Doors, their music and

their songs: they

are the practical example in Jim's life to indicate

universally any collective spiritual means of ecstasy and

mind intoxication that

people can build, and so it shall be seen.

This poem, anyway, says that the Doors embodied the

context in which those ideas were taking shape, opposed

to what Mary

and his relationship with her represented. On them and on

those ideas he leverages to overcome altogether what was

going on

with her and it all, ‘breaking on through’.

People uphold that it represents something fragile and

apparently stately as only a troubled love can be, and

that exactly this is

the central theme of the story Jim Morrison tells in the

song.

I believe that the description of a troubled love with

some fragility at the bottom, immortalized in its moment

of trespassing, is

actually one if the leading meanings of the text. But

love here is the only frangible thing: the ship is also

this, and a lover's spirit.

In the figure, this feeling is visually represented as a

force to set one free, in a forceful crystalline

appearance; the ship is not

shattered, nor it appears easy to be crushed, though the

poet's heart could be.

But in truth this love is characterized over all by some

stateliness, a far from frangible lover's spirit, which

is not just apparent,

although it leaves some permanent scars at its bottom.

This moment of sentimental trespassing is a real break

on through, to

use the proper words, which involves a concrete

acquirement of strength and overcoming, still leaving

those scars visible.

More, the surrounding lyrics and the story talk about

this love theme, but the crystal ship's

figure itself is apart from it, and it has

got nothing to do with the sentimental declarations about

Mary and Jim.

More than ever, it is a picture of breaking through in

the purest Doors sense, the symbol of the

protagonist’s decision how to

conduct his own life, both in biographic sentimental life

and emotional-active life.

But first of all, the crystal ship is the world of

expanded perceptions, of the purified inner reality

inside, the embodiment of the

strong and bright spirit of the poet and the figure of

cleansed experience which brings this spirit to come to

life and shine.

As the poet's spirit, it symbolizes the experimenting

soul, although it involves also his sentimental side (but

not directly his heart,

even if it remains as a secondary shade in background).

It represents the figure of a cleansed experience,

general, absolute, but also an individual and collective

one (first, the collective

archetype of experience itself, second, the individual

world of experience).

It is a sort of transparent shrine including it, which

leads to the polished world of perception and produces

that subjective spirit

itself. Its shining and clear sides are already

themselves that world and its purity, but at the same

time they also embody the

cleansed senses and mind swallowing it.

In conclusion, this ship of experience is inspired by the

vision of the oil tanker or plant in the ocean, all

enlightened, transformed

into Jim Morrison's own specific existential-sentimental

version of 'Etchra Condla' 's ship, and

of the intoxicated boat.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

A friend of mine, Alessandro

Amoroso, took in a lot of the suggestions for 'the

Crystal Cabinet''s involving, and

compared the crystal ship to Blake's metaphor, because

both poems express a dream of freedom, the desire of

the other side, love like a way of setting oneself free,

unbound and intact again, getting rid of reason, and a

way of changing.

But as I argued before, the figure mainly remains

referring to 'the Intoxicated Boat', in its

figurative concept,

because Rimbaud's poem already has all of these contents.

Except for the one of love: but from this, Morrison

takes the flight.

To be precise: he takes the flight from this delusional

love. Unlike Blake, and like, instead, Rimbaud. In the

french

poet's case this happens not from love, but from the

delusions of people and of the social state, who didn't

welcome the existential change and didn't permit to the

material reality to take profit of the fruits produced by

total experience, and by the systematic derangement of

all the senses.

It wouldn't allow the poet to live it in the world that

he really wants to live in: the earthly one, and forces

him in

the imagination paradise of poetry, which at length means

death, and estrangement from any reality. William

Blake, in 'the Crystal Cabinet', loses the world

of heaven, Belulah, just to end tossed out of the

Earthly world,

Eternity, through a forced rebirth of him as a

child, more in woes than crying out for a new life, and

of his lover

as a blindly suffering woman after giving birth: they

both find themselves in the hell of suffering, Ulro.

On the

contrary, the trip to the Fairyland of Etchra Condla

is a solemn promise and premise for the kings

reincarnation,

although by another part of his spirit.

Rimbaud's travel as the intoxicated boat, has no

full and happy return to the earthly world he misses: he

remains

ideally into the ocean of his boat's adventurous travels,

and at the same time he projects himself back at home

like a child playing in a water pool with a paper boat,

resigned to keep his gained freedom of existence intact

and

bring it in real life, in the restricted ways he can. Not

the ideal one, but there is a way back. The poet himself

wants

and forces it: the important thing, 'when everything

else fails' is to keep a constant personal rebellion

into his own

spirit.

The same thing does Jim: he goes straight to achieve

paradise and has all intentions to hold it, but: 'When

we get

back, I'll drop a line'. He's saying Mary that for no

reason at all his fall in experience with her has

precluded him the

earthly world and condemned him to hell.

We could say that, in the crystal ship figure,

like in the second part of Morrison's poem, Blake is just

an allusion,

just like 'crystal' is an adjective. The noun,

'ship', says of 'Etchra Condla' 's and 'the

Intoxicated Boat' 's basis.

Afterword:

a

deepest analysis of some lyrics, to complete the meaning

of the ship. Jim, Mary, and

the pure world of perception:

What does the crystal ship mean to the rest of

the text? To get this, we must go back to the verses in

the

previous strophe.

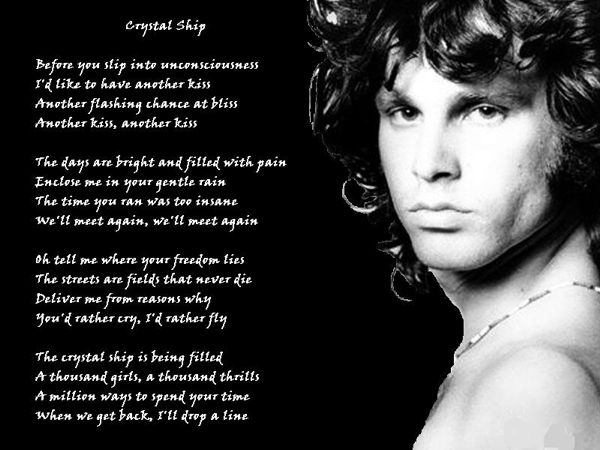

'Oh,

tell me where your freedom lies

the streets are fields that never die.'

In these lines Morrison takes the distance from his

love pain and its implication with his loved one: he says

that

the ways of experience and of life itself, which they had

both chosen, but especially hers, are wearing and

impenitent places.

That is to say, intense but also tiring, above all when

you are alone.

That question, 'where your freedom lies', is the

way off the romantic sentimental world.

The ship is exactly that freedom he's talking about, the

freedom to experience in general, freedom of

experiencing,

freedom to emotion, freedom of emotions and towards other

feelings too.

In this ship women and trips, or emotions (originally

indicated as 'pills', then changed into 'thrills'),

represent both

the actual passengers of the collective ship, and the

content of any individual's inner boat.

We'll see further that the ship's passengers (girls and

pills / thrills) are single elements of experience in

general,

collective aims, which crowd the vessel, but at the same

time other people who climb on board to take this sailing

trip, the others in this experience. The poet's spirit

trip mates (still, girls and pills / thrills) are both

other companions

and reasonable contents of the poet's mind and soul,

elements of ‘knowledge’, another crucial word

to Morrison.

In the background of this all, the picture draws a

natural sentimental fragility in experience and emotions

and for a

shattered love feeling, but at the same time it contrasts

it.

This is the feeling of a sentient animal with a fragile

but forged and reborn sensitive soul.

From this point on, all over the second part of the song,

the poem transforms into a taking of a position: Jim

states

he has made up his mind both sentimentally and

‘ideologically’.

'Deliver

me from reasons why

you'd rather cry

I'd rather fly.'

Before all, he seems deluded by her choices in life.

She prefers to cry, leave him and chase certain

ambitions, pursue

perspectives of mind & experience openings, material

& artistic, different from his, more materialistic of

those Jim

tried to dream of and plan with her (in another song,

'… the end of our elaborate plans …'),

be them sentimental or

professional.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

He wanted to walk some artistic

path with her, but not in the direction she seemed to

lead, not to be a valuable

partner for such an interest she demonstrated (the double

sensed picture which emerges in 'Twentieth Century

Fox' may be well related to this). It feels like he

saw himself as a partner that now seems an inconvenience

and

even an obstacle for possible alternate relationships or

sexual experiences. Like he felt her need for other

experiences as a pretense to leave him or take time. On

the other hand he wouldn't think of them as an obstacle

for their staying together, or at least he was beginning

to think about it that way. Now one that once seemed a

reasonable earnest need of hers, appears to be a shaded

excuse or a hiding of the fact that she doesn't love him

anymore.

Still, painfully, disarmingly sweet, he had whispered

her: “the streets (in general, but in

particular the ones of you

walk in your life) are fields that never die”.

They are wearing, they offer no shelter. But then, 'deliver

me from

reasons why...'

‘Why do you want to embrace the limited

experience world?’

He seems to tell her: 'Your plans are all the result of

this choice, not opening the doors of perception, and so

you

prefer to suffer, make existential choices that are not

needed, where no renounces would be requested'. 'Why

you'd rather cry' means, ‘Why choosing the

limited experience world?’.

'I'd rather fly': I prefer to fly in the expanded

world of perceptions, of all inclusive love and love

experiences, of

an artistic world of life and creation... with it the

poem has already become an oniric declaration, and the

oniric

detachment of Jim's from Mary’s.

It indicates the severing of his perception of experience

from the need to consider her, as his lover, a means to

access it.

Looking back, in the second strophe of the text, 'enclose

me in your gentle rain', he still aimed at it for a

last time:

the poem had begun with the statement of wanting to have

'another kiss, another flashing chance at (that)

bliss'

though just to let her 'slip into unconsciousness'.

He wants to forget her, or better, chop off his loving

bound, in part, and Mary's role as a sensuous mean of

experience, in total. He doesn't recognize her as a muse

anymore. I mean a muse in this very particular sense,

and not in the conventional one (a last chance of holding

her as a way to sentimental and perceptive bliss –

Jim

used this very line just to express, also, one of his

ways to drinking, where every glass is a bet to access

the

bliss of perception, one more moment of bliss, or to pass

the line and get into emotional and intellectual hell,

confirming that 'another chance at bliss' alludes

to the kiss, or anything else in its place, as a medium

for

accessing that dimension).

But it seems impossible to have neither the kiss nor 'a

last access to bliss', so right now, with 'Deliver me

from

reasons why / you'd rather cry, I'd rather fly' he

makes up his mind to get rid of it. It is such a radical

decision,

that he even moves away from his original desire and

intentions of pursuing a last farewell moment, from his

need of it. He gives up the idea of accessing End of

the Night's 'realms of bliss' by their tender

bound, even for a

last time. 'I'd rather fly', then: the oniric

leave-taking.

And so comes the crystal ship, which 'is being

filled', originally, with 'a thousand pills',

both in the sense that it

consists of them (there is no “of”), and in the

sense that this “of” is implied: like people,

like pills are gathering

on board, the ship is being loaded (the ship with people,

people with experience. Filled by other people, and by

thrilling experiences), about to depart.

I think the change from 'pills' to 'thrills'

wasn't just convenient for censorship reasons, but it

also shows that 'pills'

indicated rather the effect they produce, and not the

item itself. Like the ship, pills are a symbol for

both any

means you can use to get the experience and for the

experience itself (both drugs as ecstasy inducers and the

musicians- leaders of the ship) - thrills,

instead, are double sense between emotions and

intoxication: the effect

of pills, of the songs, of all the mediums built alike

the latter.

Plus, keeping 'pills' would have limited the

variety of sources for them that Morrison intended (maybe

he even

reflected better and more deeply, while recording and

before publishing “The Doors”, their

first album, which

would have meant reaching a larger base of listeners than

the clubs public).

The oniric ship of experience and of the real full

discovery of reality effects the emerging of a cleansed

crystal

shining spirit and a transparent vision with which

approaching the world.

'A million ways to spend your time' refers to all

these things together, and even if the thousand girls

aren't meant

to substitute his broken and lost relationship with Mary,

there will probably be another one who will do, no way to

think that even if he will never completely overcome his

sentimental delusion and loss of her (who does?), he'll

also still suffer for it, or won't access to a real true

love and mate forever. Jim now has decided that hers has

become a “falsely true” love, from a certain

point on... and he has been knowing her for a long time.

Among that

million ways to spend your time, anyway, rest also the

girl or girls of his future life who will substitute her.

'When we get back / I'll drop a line': the pronoun

'we' confirms that the ship is also filled with

other people who

want to acknowledge this way of living.

The poet also states that at the end of this experience

trip he's going to inform her that he's back: “I'll

drop a line”

is going to be the signal, and he will report her how it

went, too.

It the end, in their relationship, they'll meet again, at

least to reckon where their mutual choices had led them

to.

But in his frame of mind it feels like he meant: 'you'll

see that I was right!'. Maybe, when 'the insane time

she ran'

will have passed, they'll even get together again, but he

doesn't expect nor hopes for that. He doesn't even wish

for it anymore: he doesn't aim anymore at that other

"flashing chance at bliss", neither as a

last kiss of farewell.

When they'll meet again, possibly they'll put their

friendship on another level. And it all happened...

With

lots of love

to James Douglas Morrison.

Written

on December 8, 2020. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Sources, quotes and notes:

'Copyright owner for 'The Crystal Ship' 's lyrics and for

all the Doors songs lyrics above and hereby mentioned:

'The

Doors Music Company'. All rights reserved.

'The Crystal Ship' video frames published by Warner

Brothers. All rights reserved.

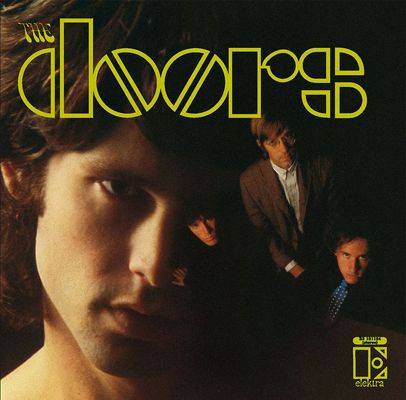

'The Crystal Ship': The Doors, 'The Doors',

Elektra Records 1967.

Other Doors lyrics quotes: 'The Crystal Ship',

'Twentieth Century Fox', 'End of the Night', 'The End' from

the Doors, 'The

Doors', Elektra Records 1967;

'The Soft Parade' from the Doors, 'The Soft

Parade', Elektra Records 1969.

For Jim Morrison's disclosing the crystal ship's origin

from Lebour na hUidre.

Description of the crystal ship's magical powers and

many other hints: Chuck Crisafulli, 'Moonlight Drive.

The stories

behind every Doors song', Carlton Books 1995, pages

28-29.

On Lebour na hUidre / The Book of the Dun Cow: 'Lebour

na huidre : Book of the Dun Cow' Hodges,

Figgis & Co. for the

Royal Irish Academy 1929; 'Lebour na huidre: Book of

the Dun Cow' (Middle Irish and English), Royal Irish

Academy 1992.

Quotes from the Connla's legend text: 'Connla of the

Golden Hair and the Fairy Maiden' from Patrick Weston

Joyce, 'Old

Celtic Romances' CreateSpace Independent Publishing

Platform 1920.

For the curragh and the Mag Mell's names: 'Lebour

na hUidre' translation by O'Beirne Crowe 1974,

information gathered

also on www.wikiwand.com/en/Echtra_Condla.

On William Blake' s poetic and 'The Crystal Cabinet':

William Blake 'Libri Profetici' Bompiani 2003.

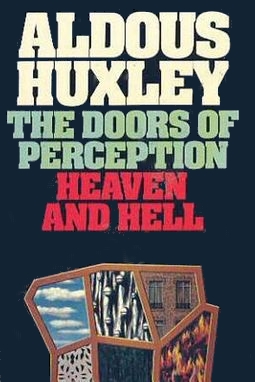

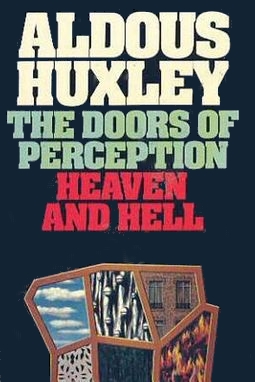

About Aldous Huxley: Aldous Huxley, 'The Doors of

Perception: And Heaven and Hell' Random UK 2006.

On Arthur Rimbaud and 'Le Bateau Ivre': Rimbaud,

'Tutte le poesie' Grandi Tascabili Economici Newton

1972.

Wallace Fowlie, 'Rimbaud, Complete Works, Selected

Letters' University of Chicago Press; new

edition 1966.

Wallace Fowlie ,'Rimbaud and Jim Morrison, the rebel

as a poet. A memoir' Duke University Press

1994, pages 48-53.

John Densmore on the crystal ship's meaning, on Jim's

question for the change of 'a thousand pills' into 'a

thousand thrills',

and many other hints: John Densmore, 'Riders on the

Storm. My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors', Deli

Publishing 1990.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

© Sonia De Pascalis for the

Doors Quarterly Magazine Online - January 2021 |

|